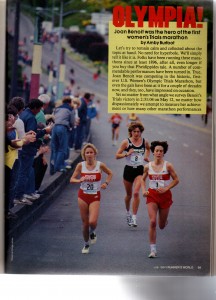

Finally. That’s what the Nike ad said on the back of the program for the first US women’s Olympic Trials marathon. Finally, women are included on the Olympic program. Finally, hundreds of distance runners have a new goal to strive for. And finally, the day for US team selection had arrived.

It was a greatly anticipated moment, to finally walk to the starting line with more than 200 other women runners. For some, this race had served as motivation to reach a tangible goal–at the least, a 2:51:16 qualifying time. For some, it was the best–not necessarily the only–choice left open for a chance at Olympic participation, for lack of other distances (5000 or 10,000 meters) to run. For only three, it could be the realization of an Olympic dream. For all, it was a momentous occasion.

Scarcely a person in Olympia had not contributed in at least a small way to the day’s festivities, if only to turn out and cheer. And cheer they did.

The 56 seeded runners took their assigned positions on the starting line, and the rest of us positioned ourselves at random behind them. There was lots of well-wishing among the women, everyone hoping for PRs in general. Nearly everyone readied watches for the countdown to the start. A notable exception was Julie Brown, who wore no watch at all. Some were obviously more concerned with place than pace.

Out for a PR myself, I didn’t dare look up for the balloons or whatever signaled the start. At the front, it was not the time to celebrate yet, just time to race. And until things steadied a little after the first mile or two, I knew I’d have to be alert to run in the thick pack. Lots of hands went up, steadying runners against tripping and crowding. No one seemed to rabbit out front. All seemed content to stay together at a reasonable pace.

While I may have thought I’d be running in a race in which I knew everyone, the truth was that I could not put many names with faces. Yet it was pleasant to recognize some faces “from the past,” like Kim Merritt, Judy Gumbs-Leydig and Katy Schilly. As Kim and I ran along together, she became upset when she registered a 6:10 mile split. (Sub-2:40s were not in the stars for either of us that day, but she managed a respectable 2:43.) Maybe it occurred to Kim, as it did to me, that had we been given this opportunity, say, prior to Montreal, we might have been Olympic teammates.

My pace seemed to hold steady until about the halfway mark or so. I knew there were more hills in the first half than in the last half, so I took heart from my early splits. I tried to concentrate on getting from one aid station to the next or from one mile marker to the next. The stations were perfect. No one had ever before handed me cups of water with caps and straws. Certainly, I had never been given sponges shaped like pineapples. In addition to a provided electrolyte drink, we were allowed personalized “specialized fluids.” My own E.R.G. awaited me every five kilometers at the very same location on the middle table. I could count on it. If all else failed, a backup table provided water for those who missed the first round.

In spite of best-laid plans, my own pace went awry. And while I’d like to say that I dropped back in the pack to experience the whole spectrum of the race, the plain truth was that the choice wasn’t mine to make. I could easily have joined the 40 or so dropouts, but I chose to experience the finish the only way I could and still salvage my screaming hamstrings–slowly.

I should not have been surprised that my body betrayed me. It was less than four weeks since my qualifying race at Boston, where I had blacked out from hypothermia, and this was my fourth marathon in as many months. I resigned myself to just finishing.

For the first time, I looked around at the beautiful scenery. There was one street, completely canopied by lush green foliage overhead. There was Capitol Dome looming over Capitol Lake, and green-forested hills all around. The streets were lined with thousands of cheering supporters.

In addition to the crowd enthusiasm, I was touched by the support of my fellow competitors. As my own race soured, I often slowed to walk , took comfort in stretching out painful muscles at the aid stations. Seemingly every runner who passed by me offered a kind word. The camaraderie was wonderful. We were bonded in a historical moment.

We were applauded for the entire last mile (it was dubbed the miracle mile). No matter our place or pace, the cheering fans reminded us more than ever what a special moment this was for each of us. After the race, in the finish area, the Olympian treatment continued as we were bedecked with flower leis, treated by medical crews and massage therapists, and supplied with food and drink. Our every need was met.

Later, a dear friend, trying to salve my disappointment, offered consolation that I wish I could share with those who had not been able to finish and others, like me, who were disappointed with their finish. We had come to run like the champions we are, she said. And no one could fault those of us who tried to run better than we ever had. It reminded me of something I said before my qualifying performance at Boston the month before:

“There’s no shame in trying and failing, only in not trying at all.”

Had the International Runners Committee / American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit for the women’s 5000- and 10,000-meter races been successful and led to inclusion of these events in the 1984 Olympic Games, the makeup and perhaps the outcome of the Olympic Trials marathon might have changed entirely. For that matter, the selection of women’s Olympic marathon teams would have been affected worldwide.

The judgement denying a preliminary injunction seeking the addition of these two events to the summer’s Games in 1984 came down April 16, 1984. On that same day, Lorraine Moller won the Boston Marathon to ensure a spot on the New Zealand Olympic marathon team. But her friend and countrywoman, Allison Roe, unable to finish Boston, would not be going to Los Angeles. Several other capable world-class runners would not find a spot on the New Zealand team either. As Moller put it, there are not enough races to go around.

Many women, including myself, were deeply disappointed by the absence of the 5000 and 10,000 in the Olympic Games. Certainly, the significance of the marathon’s inclusion should not be overlooked. But it’s ironic that, in a year in which there was a distance as long as the marathon, there were no other options for women distance runners.

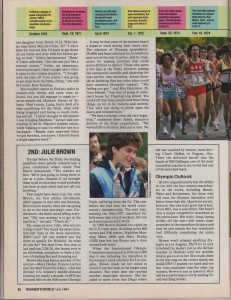

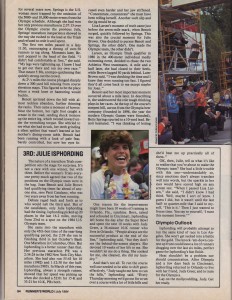

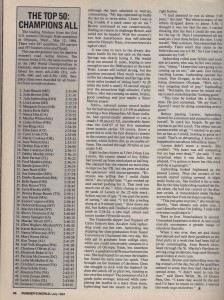

That said, this was the day to celebrate our first-ever USA Olympic Women’s Marathon team. Joan Benoit was the victor. As Amby Burfoot so aptly stated in Runner’s World’s coverage of this race: “No matter from what angle we survey Benoit’s Trials victory in 2:31:04 on May 12 (1984), no matter how dispassionately we attempt to measure her achievement or how many other marathon performances we hold it up against, the same ineluctable conclusion presents itself: The was the greatest individual marathon effort of all time.” Joan had endured a lot in the preceding weeks leading up to the most important race of her life. This included knee surgery, and as if that were not enough, her hamstring muscles tightened up in reaction to the surgery, leaving her with two potential time-bombs that could sideline her at any moment. She prevailed and in world class style. Her new teammates joining that historic team included Julie Brown (2:31:04) and Julie Isphording (2:32:26), who declared, upon finishing, that dreams do come true.